The 1960s design scene in Portland had elements that may seem familiar to designers today: passionate creatives, a small community, and a collaborative work ethic. Out of this creative pool emerged Byron Ferris, Bennet Norrbo, and Charles Politz, three men whose careers overlapped, who influenced each other and yet left their mark in distinctly different ways.

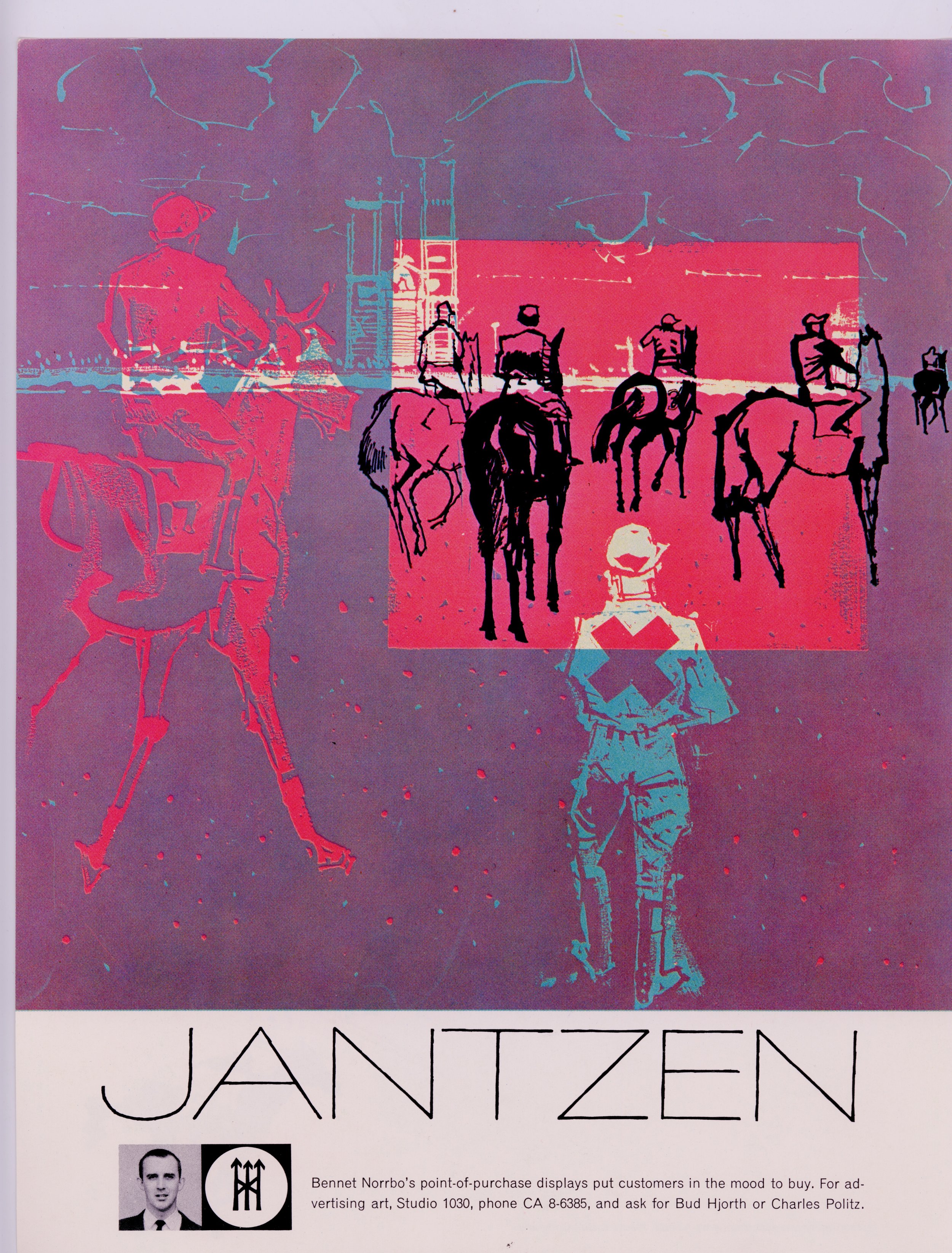

Charles, Bennet and Byron worked to develop some of Portland’s biggest brands, like Jantzen and Pendleton, defining the city’s stake in outdoor and athletic wear. As mythologized in Mad Men, the “Golden Age of Advertising” claims New York City as its epicenter. But even in Portland, advertising was changing and practitioners were defining their craft. While Portland’s ad men may have had a few things in common with their fictionalized NYC counterparts, their differences are more stark.

According to Joan Campf, a colleague of Charles Politz, the Portland creative community was more united and there was no ego. She relates that professionals in the field were honored to be doing the work they were at the national or local level.

Carol Ferris, wife of Byron, wrote, “Being a designer in the Northwest required grit and insistence.”

Studio 1030, 1960. Charles Politz, seated left. Bennet Norrbo, standing third from left. Dick Wiley, standing far right. Joe Erceg, standing second from right, far back.

Joe Erceg, colleague of Bennet and Charles spoke about there being one main independent studio in the 1960s, “Studio 1030 was right across the street from Powell’s Books (in the old Fez Ballroom) and I rented a room there. There were illustrators and re-touchers. Dick Wiley was there (illustrator of Dick & Jane books) and he would hire us to do modeling. There also was Tad Putman who did furniture illustration, Bennet Norrbo and Mark Norrander. That studio ran for several years before people moved on. It was there that these guys became very good at their craft.”

What made Portland’s ad men so great?

They Were Artists.

Byron, Charles and Bennet were artists, illustrators, curators, critics, and collectors in their own right. As Byron Ferris wrote in his 1966 book, Fell’s Guide to Commercial Art, “The first commercial artists, just a few generations ago, were recruited from the ranks of fine artists. Easel painters produced pictures to glamorize products, and sign painters did imaginative lettering.”

Byron’s artistic talent was expressed at a young age as he formed the “Korny Kartoon Klub” at Jefferson High School in 1939. All men produced fine art simultaneously with commercial work, and with equal pride.

Byron once said of Charles Politz that he liked “that a designer could also be a gallery artist of note. He simply loved all art and ignored the barrier of thought which separates gallery art from art for use.”

Charles was known for figurative drawing, developing his own technique using a stick, ink, and quick gestures. Bennet devoted himself fully to fine art in his later years, creating striking paintings under his own name, AND his alter-ego: Joe Hat.

Charles Politz stick drawing

painting by Bennet Norrbo (Joe Hat)

They Were Opinionated.

“My three general aims are these: to be thorn in the side of the avant grade, to be a champion of the rights of you middle classes, and last and certainly not least, to be society’s darling,” wrote Bennet Norrbo.

This quote hints at Bennet’s conflicting ideas of what it is to be an artist, and his playful and rebellious style. Marilyn Murdoch, his longtime friend and executor says Bennet was at the same time crude, sensitive and hilarious.

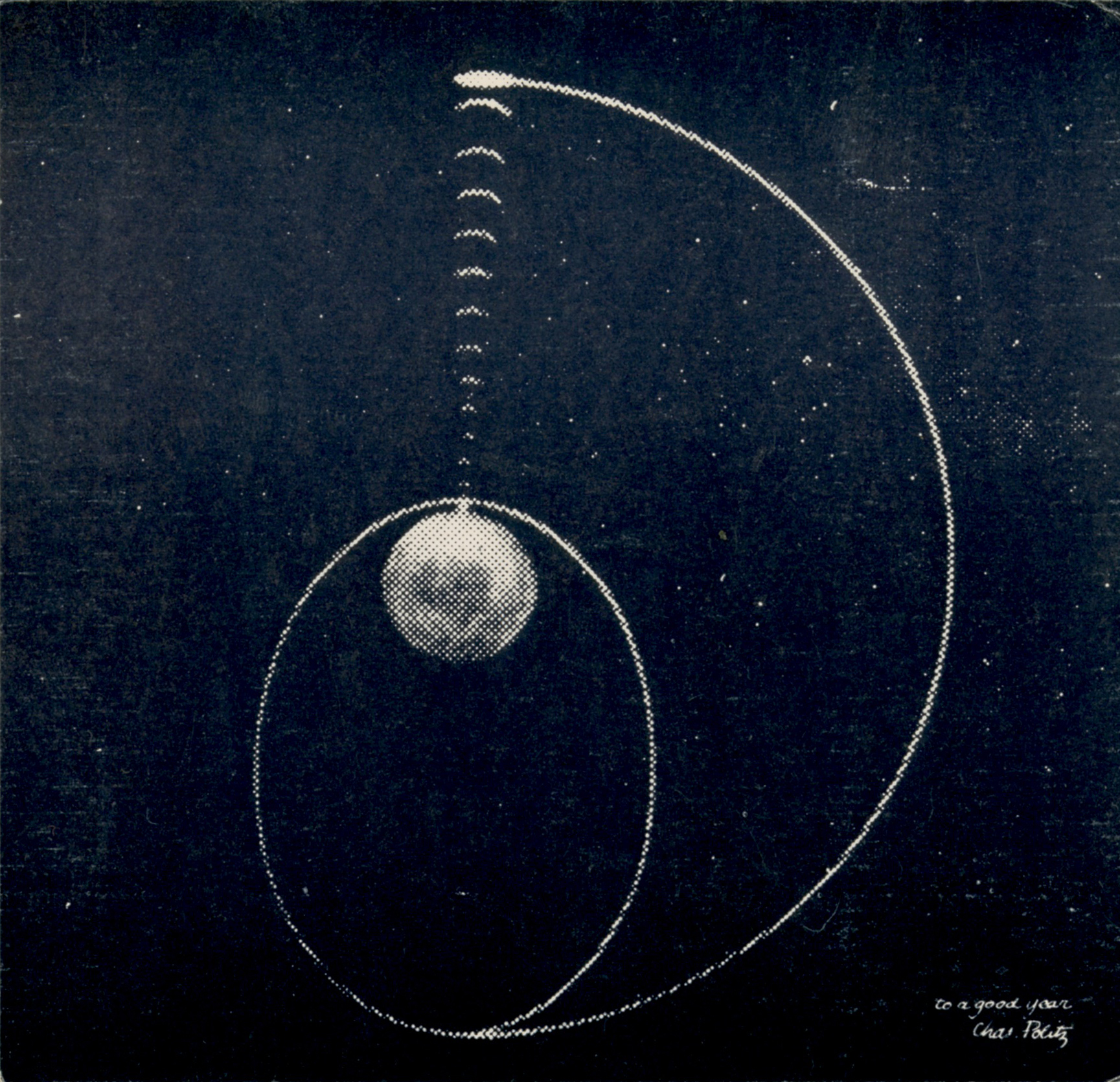

Charles Politz expressed his ideas and sharp wit through his yearly New Year’s card which he produced every year for six decades. “S.Claus, the A-Bomb, & I hope to see you around for yet another Very Merry Xmas,” he wrote in 1945.

Charles Politz, 1945 New Year’s Card

Charles Politz card celebrating the launch of Sputnik

Byron’s writing, while witty, was more academic as it related to design. Byron wrote and spoke about the work of Portland designers nationally, putting Northwest design on the map through Communication Arts magazine and the Aspen Design Conference.

They Loved Portland.

While all men traveled and lived other places, they called Portland home for the greatest part of their lives. They engaged with the community in different ways.

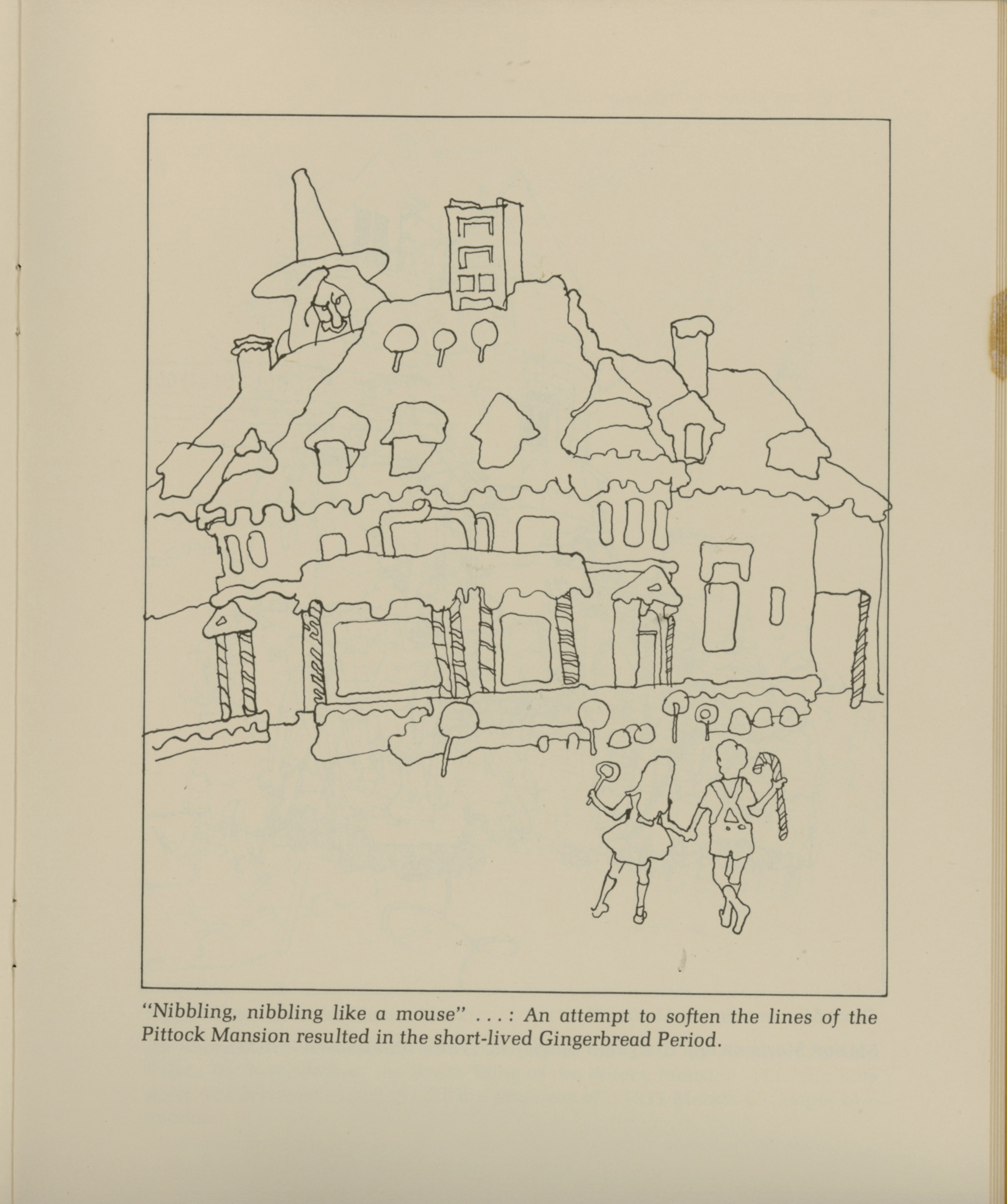

Bennet (who stayed single), preferred Portland’s “seedy” establishments to domestic life. That scene inspired his painting and writings. He once wrote and published a pamphlet that told a ridiculously fictional history of Pittock Mansion complete with comic illustrations of monster attacks and Roman ruins (yes, he was a zinester)!

Bennet Norrbo’s “Pittock Mansion” zine

Charles thought critically about the changes in Portland and wrote a satirical article for The Oregonian on the East/West Portland divide. He was also chosen as designer and curator of the Oregon Centennial photography exhibition.

Charles Politz (standing left) planning the Oregon Centennial exhibition

Byron wrote a regular column called Design Sense for the magazine of The Oregonian and Charles and Byron together tackled branding projects for Pioneer Square, Portland Opera and the Cultural District.

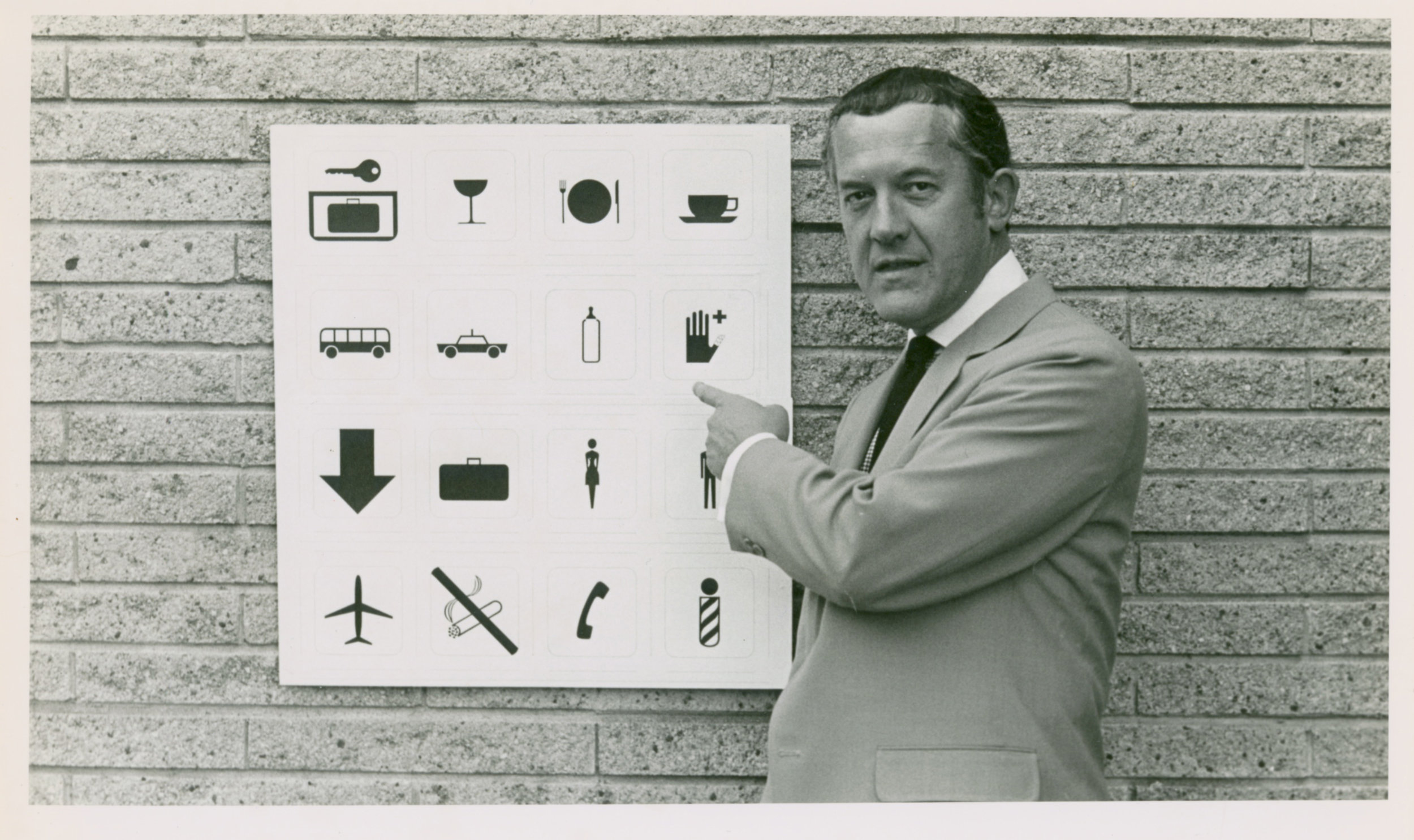

Byron Ferris presenting an icon set for the Portland Airport

They were all deeply ensconced in Portland’s culture—at times celebrating it, and at times rebelling against it.

Joe Erceg said that the creatives in Portland didn’t really compare themselves to New York City’s advertising scene, “We knew where the big league was, we were in the minor leagues. It was fine because that was the level that the business was, but that didn’t mean we didn’t do good work.”

Portland Design in the 1960s is a series developed by Portland designer Melissa Delzio. It was originally inspired by her Design Week Portland event titled “Portland Designers in the Mad Men Era”. Here’s a short list of 1960s designers we might feature next: Doug Lynch, Greg Holly, Dick Wiley, Joe Erceg, Timothy Leigh, Milli Eaton, Pier Mellara, Thomas Lincoln, Lloyd Reynolds, and Mark Norrander. If you have a recommendation on who we should feature, please reach out to: melissa@meldel.com.