Marvelous Marilyn. That’s what they called her at Portland’s influential freelancers collective, Studio 1030, where Marilyn Holsinger was the group’s only woman artist in 1960. Marilyn was marvelous by all accounts, but also a serious career woman. She held 11 design positions across 40 years and three states. She worked for ad agencies, newspapers and universities. Her clients included: Meier & Frank, Viewmaster, Revlon, the San Francisco Examiner, Oregon State University (OSU) and countless others. The references on her resume are a list of who’s who in the Portland design scene of that era. She was exuberant and stylish, athletic and a natural leader. She was cracking the glass ceiling just by showing up and doing her best work with grace. “I don’t remember her feeling like what she was doing was groundbreaking,” reflects her daughter Joan. “If anything she was just a woman before her time.”

DISCOVERING THE DRAWING BOARD AND THE SKI SLOPES

Marilyn was born and raised in Lincoln, Nebraska. Her family made the move to Portland in 1934 after Marilyn’s mother had seen a picture of Portland in Sunset Magazine. Marilyn (then 12 years old) was at first upset by the move, and her parents gave her a wire-haired terrier named Mugs to help her adapt. The family settled in NE Portland in the Sabin neighborhood and Marilyn attended Sabin School, then Grant High School.

In addition to the new pup, drawing also helped Marilyn transition to the Pacific Northwest. She was always drawing. Once in high school, she discovered a usefulness for her drawings: creating illustrations for her high school paper. Also in high school, she became a skier and was one of the first to ski at Timberline Lodge in 1938. According to Joan, “One her favorite memories was piling in the back of a pick-up truck to go to the snow in high school — no seatbelt of course. They’d hike up in the snow (no chairlifts!) and ski down. No wonder she was always trim and fit then.”

Marilyn knew she wanted to be an artist, and her parents encouraged her, even as war broke out in Europe. Marilyn graduated from high school in 1940, with optimism, talent and a dream.

“Miki” from the UO Yearbook.

Marilyn had decided to attend the University of Oregon (UO) and major in drawing and painting. Now known by her nickname, Miki, Marilyn was described as vivacious, and exuded confidence with her Judy Garland-esqe haircut. Joan recalls that Marilyn’s father “…was very supportive of her attending UO. But one time she got quite tipsy at a holiday dance and threw up in the potted palm tree in the lobby of the Multnomah Hotel, today an Embassy Suites. ‘Never again’ he said, or he’d withdraw her college fund.” It is unknown if she actually heeded her father’s warning, but it is clear from her records that Marilyn didn’t let a good time get in the way of her studies, and vice versa.

She distinguished herself right away, becoming president of the Association of Women Students and vice-president of Alpha Chi Omega Sorority. She was recognized by the Motar Board (an honor society for women) as an outstanding student in scholarship, leadership, and service.

By 1943, men were leaving for war and women were stepping up to take their places in all facets of life, on campus and off. Marilyn graduated in 1944, and with all of her leadership and business experience, she was ready for the workplace.

Her first job out of school was for the The Oregon Journal (Portland’s daily newspaper until 1982) as a “promotion artist”. While trained as a fine artist, at The Oregon Journal she tried her hand a wide variety of projects in this new realm of graphic arts. According to a letter of recommendation from her supervisor, “At The Journal Marilyn did newspaper layouts, black and white drawings for advertising and editorial use, designed direct mail pieces in color, made posters and did book illustrations. She is a capable commercial artist with a varied experience. Without reservations I can commend her for employment.”

In 1946, after two years with The Journal, Marilyn left the safety of her Portland home and her stable job to be a “big city career girl” in San Francisco.

A WOMAN BEFORE HER TIME

With newfound confidence in her role as a promotion artist, Marilyn and a handful of girlfriends from college set out for San Francisco. The friends all lived together in a house in the Mission District. It was 1946 and many of the men returning from war went straight to college thanks to the GI Bill, leaving a gap in the workforce. It was this gap that helped enable Marilyn and her friends to quickly acquire work in their field.

Within a month of arriving, Marilyn landed her first job in California at Hubbard and Baird, a commercial art studio. Harley Jessup, a student of Marilyn’s later in life, remembers her stories from this period. “She mentioned that as the only woman in the office she would inevitably be expected to make the coffee in the morning. She felt she had no choice but to put up with it. Her patience with that kind of nonsense was long gone by the time I met her and I loved hearing her articulately correct a client who was talking down to her.”

Not one to stand still for long, Marilyn jumped around from job to job every year or so — from advertising agencies to print shops to newspapers — earning rave reviews along the way. But the job changes were not always Marilyn’s decision. Her boss at one advertising agency during this period called her into his office and laid her off without warning. “I need someone I can talk football with,” he explained. The San Francisco 49ers had just been founded and in the days before Title VII (which was passed in 1964) you could indeed fire someone simply based on their sex (or sports preference, apparently).

Joan relates, “In retrospect, she realized that there were aspects of the (working) climate that were wrong.” But, what was certainly a setback didn’t derail Marilyn. It seems as though there was always work to be had, and Marilyn had talent and experience on her side.

She settled with Hearst Advertising in 1951, the same year that the notorious proprietor of the company, William Randolph Hearst, died. Hearst Advertising was the advertising arm of the San Francisco Examiner, a daily newspaper. Marilyn was creating illustrations for clients such as Saks, Revlon and other fashion and retail advertisers. This was a time when women were mostly used to design and sell things made for other women. Joan says, “She would model shoes for The Examiner because she had tiny size 5–1/2 feet. She had a TON of shoes!” When she finally left The Examiner in 1958, her colleagues presented her with a going away present: “one of her peep-toe pumps, bronzed and mounted on a plaque in her honor.”Marilyn was very proud of her early years with the paper and held on to that plaque her whole life.

Print piece Marilyn designed for The Examiner.

Marilyn and her girlfriends were very close in those early days, in a new city with their new careers. The post-war years were all about booming advertising agencies, martinis, and bridge parties. As years went on, the girls started to get married (three of them even shared the same wedding dress, in the frugal post-war years). Marilyn herself married Frank Holsinger in 1949 and in 1956, moved out to a mid-century modern house in Marin County, where she had her daughter. But her marriage didn’t last and Marilyn decided her days as a “big city career girl” in San Francisco were over. A newly single mother, she packed up her Hillman (gasp what a beauty!) and drove with Joan from Marin back to Portland in 1959.

BECOMING MARVELOUS

Once in Portland, Marilyn had the support of her retired parents who (along with subsidized daycare) cared for Joan, enabling her to continue her career. This may be common practice for working women now, but was rare for 1960. Her Portland career in the 60s was short, but boy was she busy! In the five years after returning from San Francisco, she worked at three different jobs, acquired her masters degree, and maintained freelance clients and a board position for the Portland Art Directors Club, all while raising a daughter.

Her first official job in Portland was with Studio 1030. If you’ve been following this series, you know that Studio 1030 was a collective of independent designers, illustrators, photographers, etc. who managed their own projects, but also collaborated collectively. Marilyn was the sole woman at Studio 1030.

Her duties there ran the gamut from receptionist to project manager, to assistant to the art director. On her resume, she called herself a graphic designer, which is likely the position she sought at the time. After all, Marilyn was not a beginner. With her slim figure, short hair and cat eye glasses, Marilyn had already been a working designer for 15 years. She had taken San Francisco by storm, working for some of the top agencies during the post-war years. But in Portland, at Studio 1030, she was relegated mostly to admin duties, squeezing in time at the drawing board when she could. It’s possible that moving to Portland set her career back a notch. There were fewer woman in the design industry in Portland compared to San Francisco. It was 1960 and The Feminine Mystique had yet to be published. “The struggle to be recognized and be taken seriously as a professional is the desire, the goal and motivation of a designer,” Marilyn said in a 1978 article, reflecting on her work. It is hard to know if her sentiment applied more so to her as a woman, or more generally as an artist in the newly defined field of commercial arts.

Studio 1030 produced promotional sheets for all their artists, and thanks to Joan, I now have the full collection! The promotional sheet about Marilyn states, “Marvelous Marilyn: Studio 1030’s only woman artist, Marilyn Holsinger, alternates between the telephone and the drawing board. Marilyn is the Studio’s receptionist and assistant to Jack Myers, Executive Art Director. Marilyn keeps tabs on the work being done by the other 14 artists at Studio 1030, so that she can answer clients’ questions and type the invoices. In addition to assembly, Marilyn orders typography, photo-stats, and generally combines all the elements which go in to the final mechanical.”

Friend and colleague Jack Myers was the ringleader at Studio 1030 and would have Marilyn work on mechanicals and pre-press. Together they tackled clients such as Viewmaster.

While not fully recognized for her own design work, given her many duties and the collaborative nature of the studio, Marilyn made good friends and valuable connections at Studio 1030. Then she jumped around again, working as an illustrator for Ken Weber Advertising in 1961, and in the advertising department at iconic Oregon retailer Meier and Frank in 1962.

This ad for Meier & Frank was designed during the period Marilyn was employed. While I cannot verify that this was her hand, with her reputation for shoe illustration, it seems likely that it was.

Marilyn’s career trajectory changed in 1963 when she was awarded the Ford Foundation Fellowship, which allowed her to get an accelerated Master’s Degree (MAT) at Reed College in teaching art. There, she was taught by famed Reed professor Lloyd Reynolds. Like other Portland Design History interviewees, Marilyn cited Lloyd Reynolds as a strong influence. His calligraphy class turned her on to a whole different aspect of her profession. “That changed her life forever,” Joan says, “she became a wonderful calligrapher. It became her avocation and her love.” In a Reed college article, Marilyn is quoted as saying, “Having Lloyd Reynolds as my teacher not only gave my artwork a new skill (calligraphy), but also gave me a fulfilling new philosophy of life.” Her friendship with Lloyd Reynolds lasted long after she graduated, and she regularly attended workshops and retreats with him decades later.

It was also during this time when Marilyn fell in love with teaching. She began teaching evening classes, while still working as a freelancer in Portland, and raising Joan.

She achieved her masters degree in 1964 and she left Portland for a federally funded grant program, creating graphics for Teaching Research at Western Oregon University in Monmouth, and then landed the publications designer position at Oregon State University in Corvallis in 1970, which is where she stayed for 10 years. Marilyn was finally setting down roots.

BOUNCING THE LETTERS

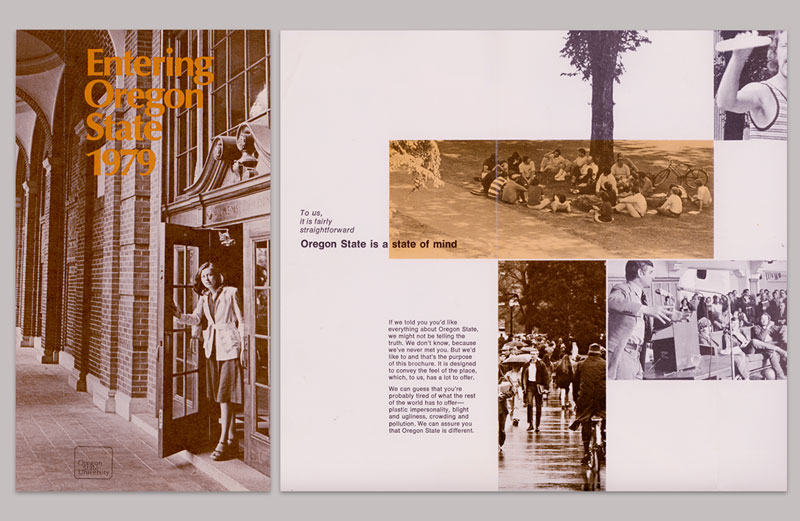

OSU College Pamphlet designed and directed by Marilyn, which also features the logo she designed.

At OSU, she was responsible for the design, production and art direction of promotional and internal publications, including the typographic logo the university used throughout the 70’s; and book covers for the OSU press. She often incorporated her knowledge of calligraphy into her work. On publication design, Marilyn was quoted in a 1978 article as saying, “Publications usually serve two purposes, promotional and usefulness. The challenge is to take an idea in a disorganized state and change it into an attractive publication that people want to read.” On finding inspiration, the article relates, “Some of her ideas stem from observations she has while jogging. She likes to run about 15 miles a week.” She said, “Sometimes something you see will trigger the connection. New ideas are just combinations of old ideas.”

Marilyn understood that design was a collaborative process with the client. She is quoted in a book saying, “Sometimes you say the craziest things possible in these meetings just to get across ideas. That’s what your job is, to get across ideas. You meet like this so minds can spin off, act as foils for the development of ideas” Like all designers, Marilyn struggled to balance the client’s demands with her ideas of how to design effective communication. “Sometimes it is not easy to find an idea that a client will like, so the designer must compromise and create a design that will get the job done.” Marilyn explained. Designers of today can relate.

Harley Jessup (now an Academy Award winning production designer and visual effects art director at Pixar) was a student and intern in Marilyn’s office at OSU in the 1970s. Harley remembers,“Her friends at OSU were all artists, designers and writers and she opened my eyes to a world of design and art that I didn’t know existed. Her taste in design was flawless and her redesign of the university logo in 1972 made an elegant statement that reflected all of Marilyn’s quiet brilliance.

Her devotion to her daughter Joan was central to her life and I heard about some of her struggles early on as a single mother working in the very chauvinistic world of advertising design. What I remember most about Marilyn though is her charm, her laugh, her talent, bright intelligence — and especially her generosity of spirit toward an awkward 19 year old OSU student at just the right time.”

Marilyn was very particular with letterforms. Her calligraphy was featured in the book, The Design of Advertising by Roy Paul Nelson and she is cited as critiquing it. The passage reads, “This is a first try. For this word, Holsinger would redo the c to make it as heavy as the other letters. And, to stress the informality of this lettering, should would bounce the letters a bit. Right now they line up too severely, she feels.” In another book on communication, Marilyn speaks about the role of typography. “I consider type an art in itself. It is greatly underrated. It is a mood setter along with the illustrations, the paper, the photos, the size, the color, the whole impact of the piece. They all create a mood, but type is central to what kind of impression the publication will make, and to how the reader will respond.”

After 9 years working as a staff designer for OSU, and teaching part-time two evenings a week while her daughter was growing up, (at Bush Barn in Salem, and at Linn Benton Community College) Marilyn transitioned full-time into teaching. She taught calligraphy, lettering, and graphic design at OSU before accepting her final position at age 60 at the University of Missouri in Columbia. There she taught Lynn Giunta, now a lettering artist for Hallmark, who recalls, “One of my Marilyn memories is that she didn’t like how Missouri made you get your car inspected before you could get your tags renewed. I’m not sure if she thought her Volvo wouldn’t pass inspection or if she just ran out of time. For whatever reason, she used her excellent comping skills to render a new up to date tag to put on her license plate. I’m pretty sure one of her students was in the car with her when the policeman pulled her over. He admitted that he couldn’t tell exactly what wasn’t right with her car tag, but he was sure something wasn’t legit and that she’d better get a current tag.”

Marilyn as a teacher.

MARILYN IN MOTION

Marilyn was a force. She was an artist, calligrapher, advocate, organizer, mentor, academic and a consummate professional. She was always in motion. She survived breast cancer and a leg fracture from a ski accident, but continued on as a cross country skier and a runner. She competed in many road races and earned awards in her age group until she was 68.

Marilyn passed away just last year. I wish I’d had the chance to ask Marilyn directly what it was like to enter the job market in the midst of WWII, about those early San Francisco years, or how it was to work as the sole woman at Studio 1030. I can only deduce from the glimmer in her eye and the cocktail in her hand that she was not one to wait around for life to happen to her, rather she ran at it with a pen.

Over her decades practicing calligraphy, she illustrated many quotations that she jotted down in notebooks over the years. Her obituary used this one,

“You gain strength, courage and confidence by every experience in which you truly stop to look fear in the face…you must do the thing you think you cannot do.” ~Eleanor Roosevelt

—

Big thank you to Joan and Enrique Sotomayor for allowing me to interview them about Marilyn and dive into their storage unit.

Portland Design in the 1960s is a series developed by Portland designer Melissa Delzio. It was originally inspired by her Design Week Portland event titled “Portland Designers in the Mad Men Era”. Here’s a short list of 1960s designers we might feature next: Doug Lynch, Greg Holly, Dick Wiley, Joe Erceg, Timothy Leigh, Milli Eaton, Pier Mellara, Lloyd Reynolds, and Mark Norrander. If you have a recommendation on who we should feature, please reach out to: melissa@meldel.com.