If a council were formed to determine a list of the “Founding Fathers” of the Portland design community, Byron Ferris’s name would have to be near the top of that list. Sure, there were others who grew to be big-wigs in advertising, but you’d be hard pressed to find someone as talented, influential and well-loved as Byron.

Born in Portland in 1921, Byron’s creativity and organizational skills developed early; he drew his first cartoons for his classmates and for money at age nine. While attending Jefferson High School, class of 1939, he formed the Korny Kartoon Klub with fellow schoolmates which kicked off a lifetime of writing, entertaining, drawing and telling “korny” jokes. For Byron Ferris, who later be known as Portland’s “Dean of Design”, humor was always critical.

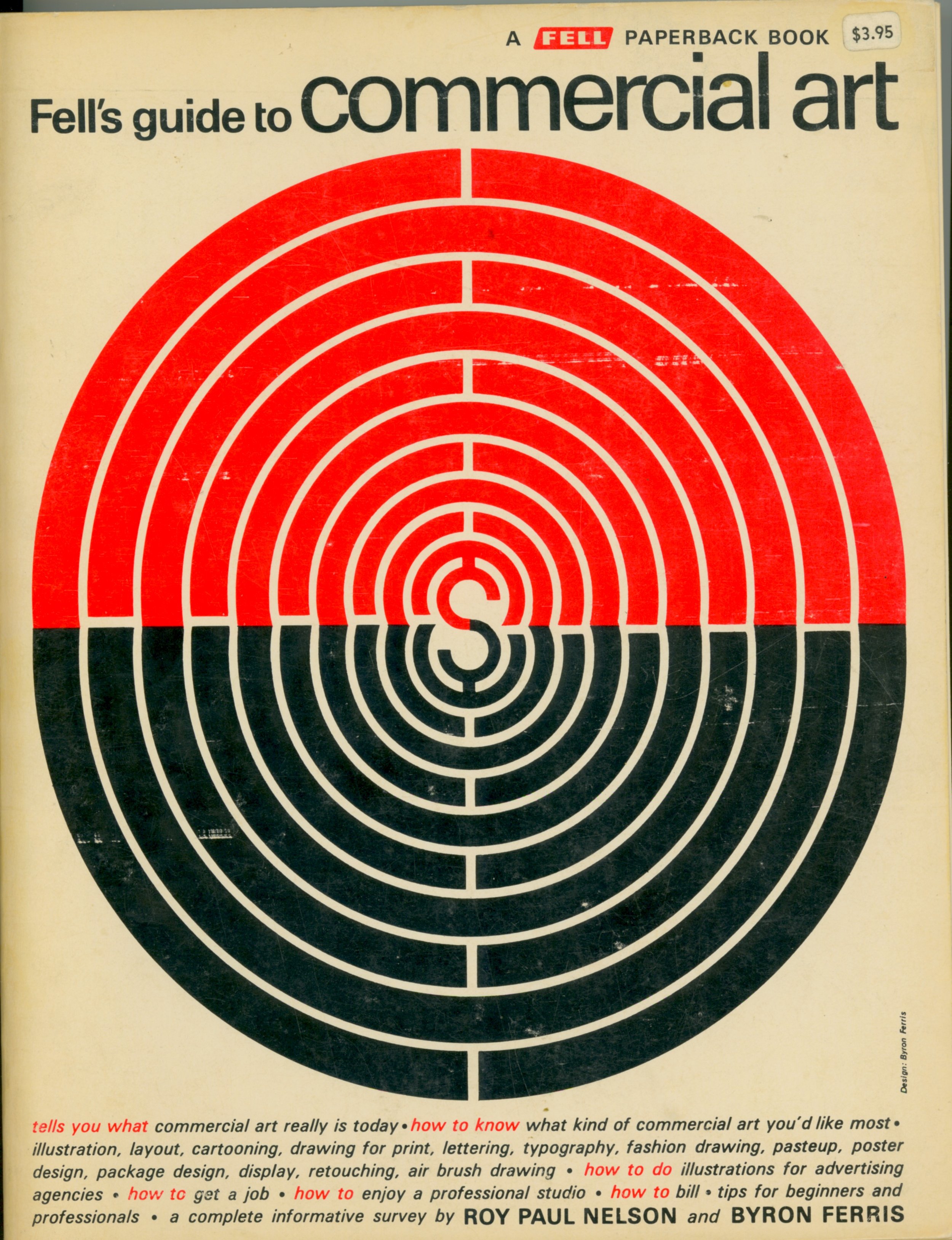

He Wrote the Book

“Advertising today displays examples of the professional artist’s work more than any other field in art,” Byron Ferris wrote in a 1955 magazine article geared at aspiring advertising artists. He continued, “In addition to understanding the craft of producing art for reproduction, the advertising artist must offer in his work a solution to communicating the advertiser’s message to the reader. Finding these solutions and adding his own ideas and personality to his work can be very gratifying. The good commercial artist who expects to make progress never stops studying—whether in regular classes, workshops, in studio groups or on his own.”

In 1955, Byron was 34. He was working as a freelance designer, was president of the Portland Advertising Artists Guild, and was clearly following his own advice. Byron, a natural teacher, began as a design and letterform instructor at the Museum Art School (now PNCA) in 1959, joining the likes of famous calligraphy instructor Lloyd Reynolds, and designer Douglas Lynch.

Former PNCA President Sally Lawrence recalls Byron’s strength as, “the power of all his years of teaching delivered in his calm, intelligent, genuine, and caring manner.” By the 1960s, Byron Ferris co-wrote THE book on commercial art during the golden age of advertising, titled “Fell’s Guide to Advertising.”

Byron never stopped writing. In the 1960s he teamed up with designers Dick and Jeane Coyle and become Associate Editor of the new and already influential Communication Artsmagazine.

He later become known for his Oregonian Magazine series about design and culture, which he later self-published as Sense of Design and some Non-sense. A quote from his introduction read, “Laughter can be aspirin for the pain of accepting a newly realized thought.”

Byron’s jokes, puns and general sense of humor were not limited to his personal life, they were abundantly applied to his work as well.

He Brought the Sizzle

In 1967 he started a firm with partner Roger Bachman, appropriately named Bachman/Ferris. The firm’s accounts included such clients as Old Spaghetti Factory, Hannah International, and Port of Portland. The successful shop was eventually sold to McCann Erickson (a familiar storyline in those days).

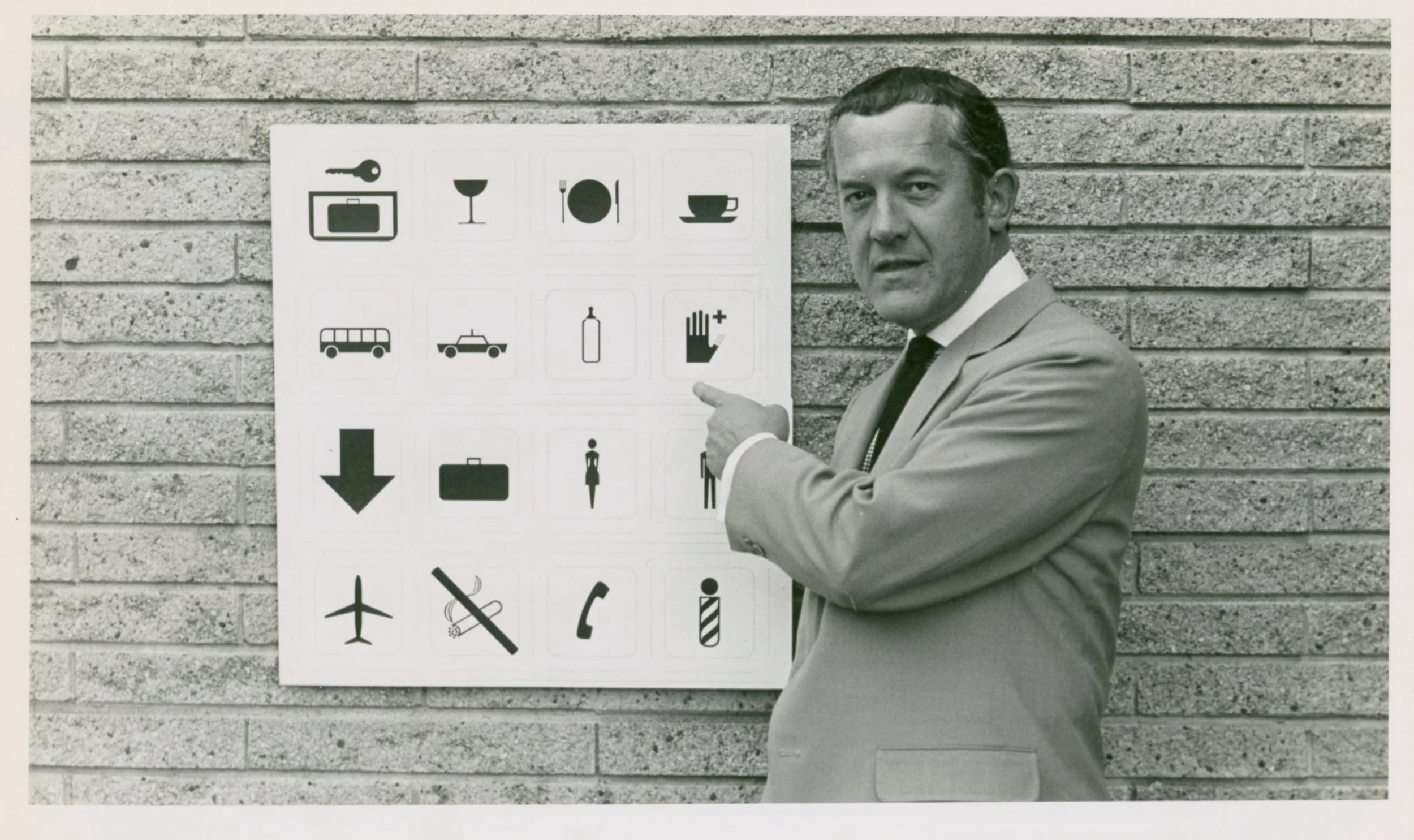

Byron presenting icon designs to the Portland Airport

“Roger Bachman and Byron Ferris hired me in 1969,” Meridel Prideaux, a co-worker, mentee and friend of Byron for many decades recalled. “They had a boutique advertising agency, and they hired me as a production manager. Roger Bachman was the total opposite of Byron but they were such good partners for many years. Roger got in at 7am and left at 3pm. Byron got in at 10am and left at 9pm or later. Roger would give assignments to Byron at say, 3pm in the afternoon. Byron would stay until 11pm, so that when Roger got in at 7, he had this layout done that would knock your socks off. The layouts sold. Byron was a real showman and a salesman. He had European style. He was very convincing. He would tell stories and make you fall in love. Roger’s part of the presentation would be market research, the demographics, etc. When Byron would present, he would add the sizzle.”

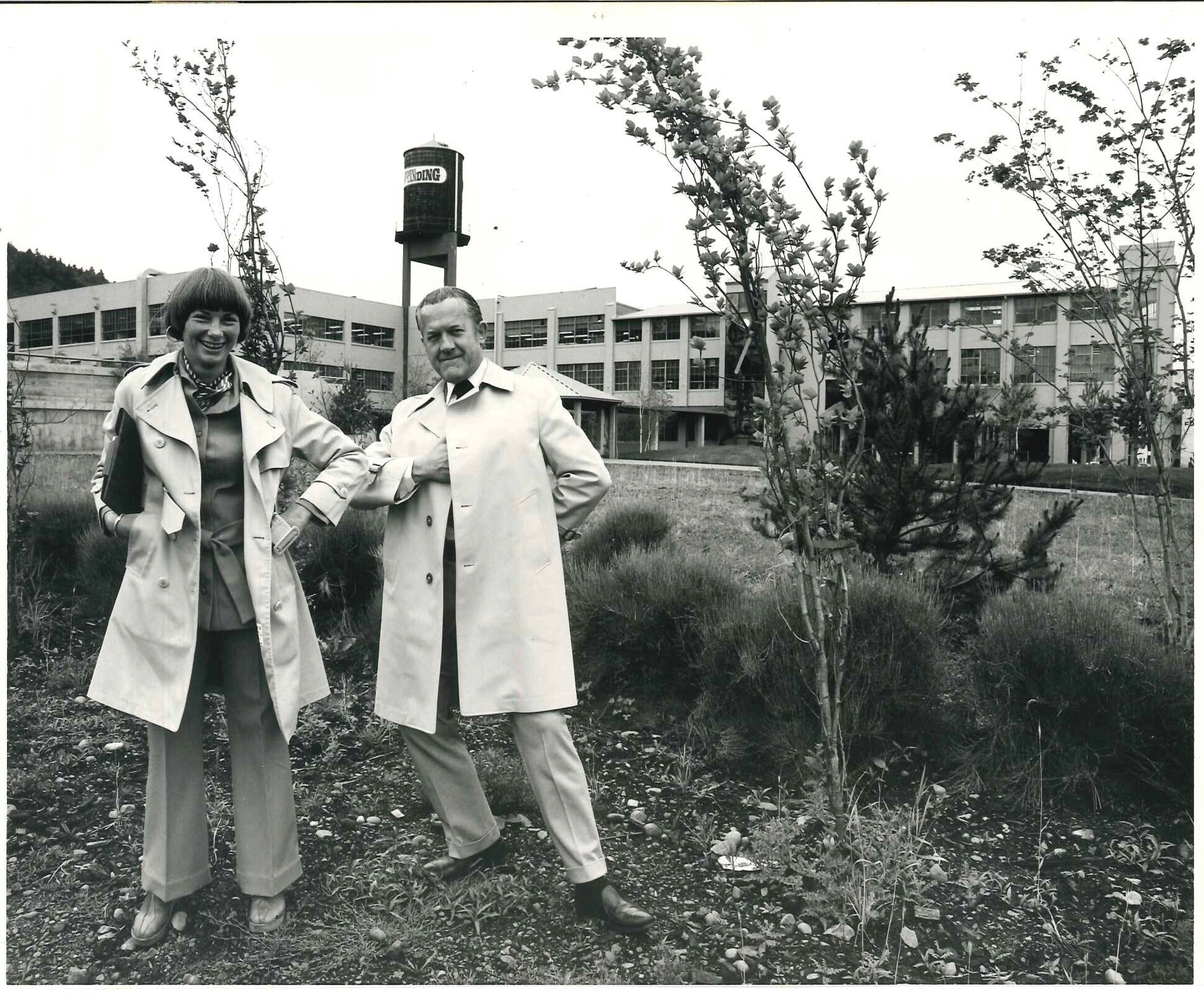

Meridel and Byron at Johns Landing on a photo shoot from Bachman/Ferris days, 1969.

“When we were at McCann Erickson, we lived Mad Men,” Meridel remembered. “We dressed like that; the furniture was like that; the style was the same. When McCann bought us, we grew to 250 people—the largest agency in Portland at that time. We had two floors; everyone smoked at their desk. The men, you would sit down at their desk, and they would pull their whiskey out from the drawer. There were no women in important positions. We were production managers, media buyers, copywriters, and stylists. Roger, Byron and I only stayed at McCann for two years. Roger and Byron hated working for McCann. New York was telling them what they could and could not do. We had handled political campaigns before when it was Bachman/Ferris. We did George McGovern for the State of Oregon and other Democrats. At McCann, they were all Republicans. They didn’t like us doing that. So Roger and Byron just looked at each other and said, ‘Let’s leave.'”

“This isn’t nostalgia: it’s the foundation on which today’s design and ad business was built.”

After McCann, Meridel continued to work with Byron on a freelance basis from the same offices, and they often pitched clients together.

“Byron would do these daily walkabouts, where he went around the office to each person’s desk, tell his daily joke and visit with them,” Meridel said. “‘Why did the chicken cross the road? To get to the other side’ was one such joke that she heard every month for about 40 years.”

“Relationships were important.” Byron’s wife, Carol Ferris, said of that time. “Designers in the 60s were also a part of a larger community, they weren’t isolated to the blue light of their computer screens yet. They were connected through working relationships with photographers, engravers, typesetters, copy editors, writers, and the cab drivers who ferried copy and proofs to and from the craftsmen to the accounts. This isn’t nostalgia: it’s the foundation on which today’s design and ad business was built.”

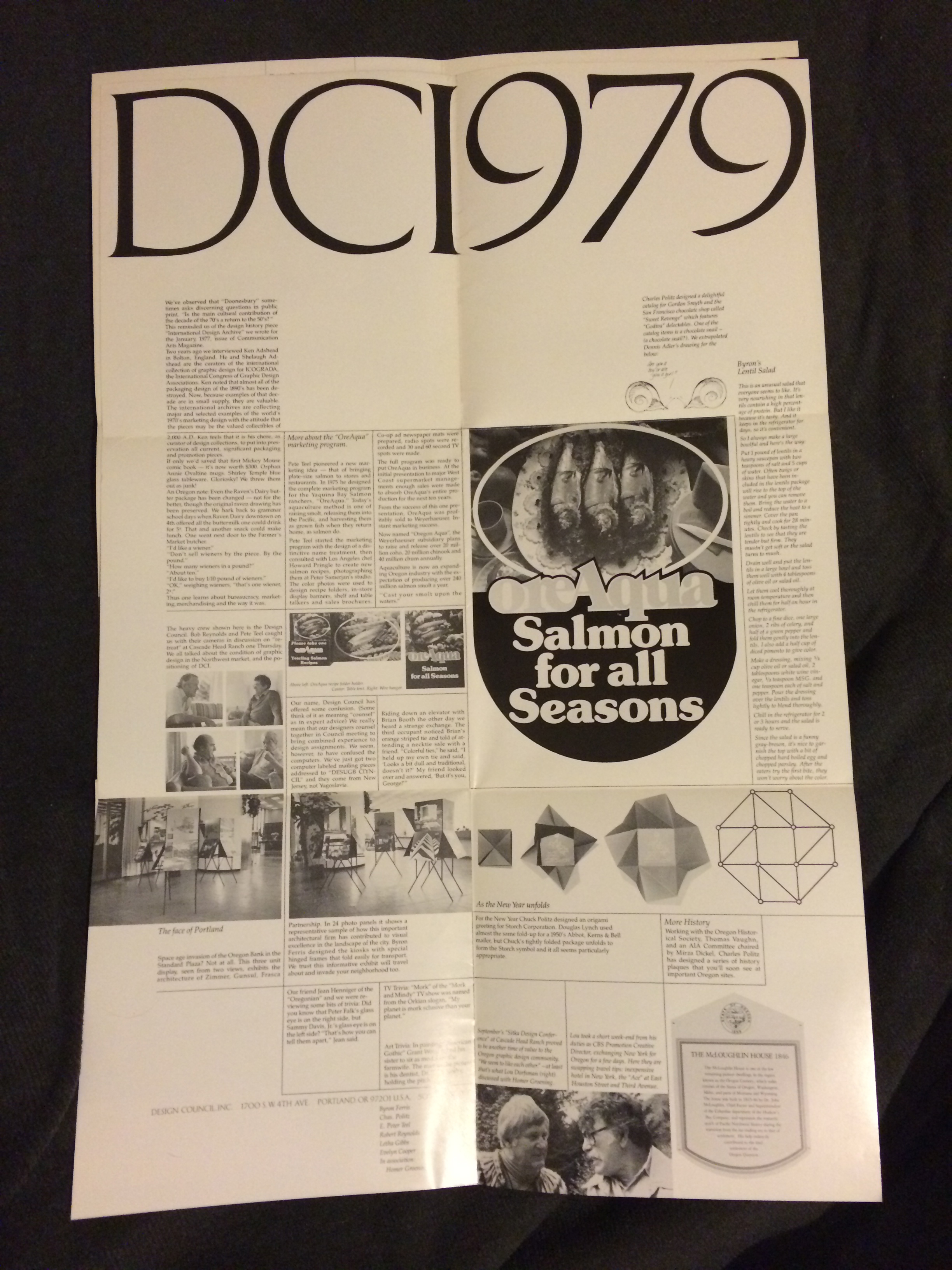

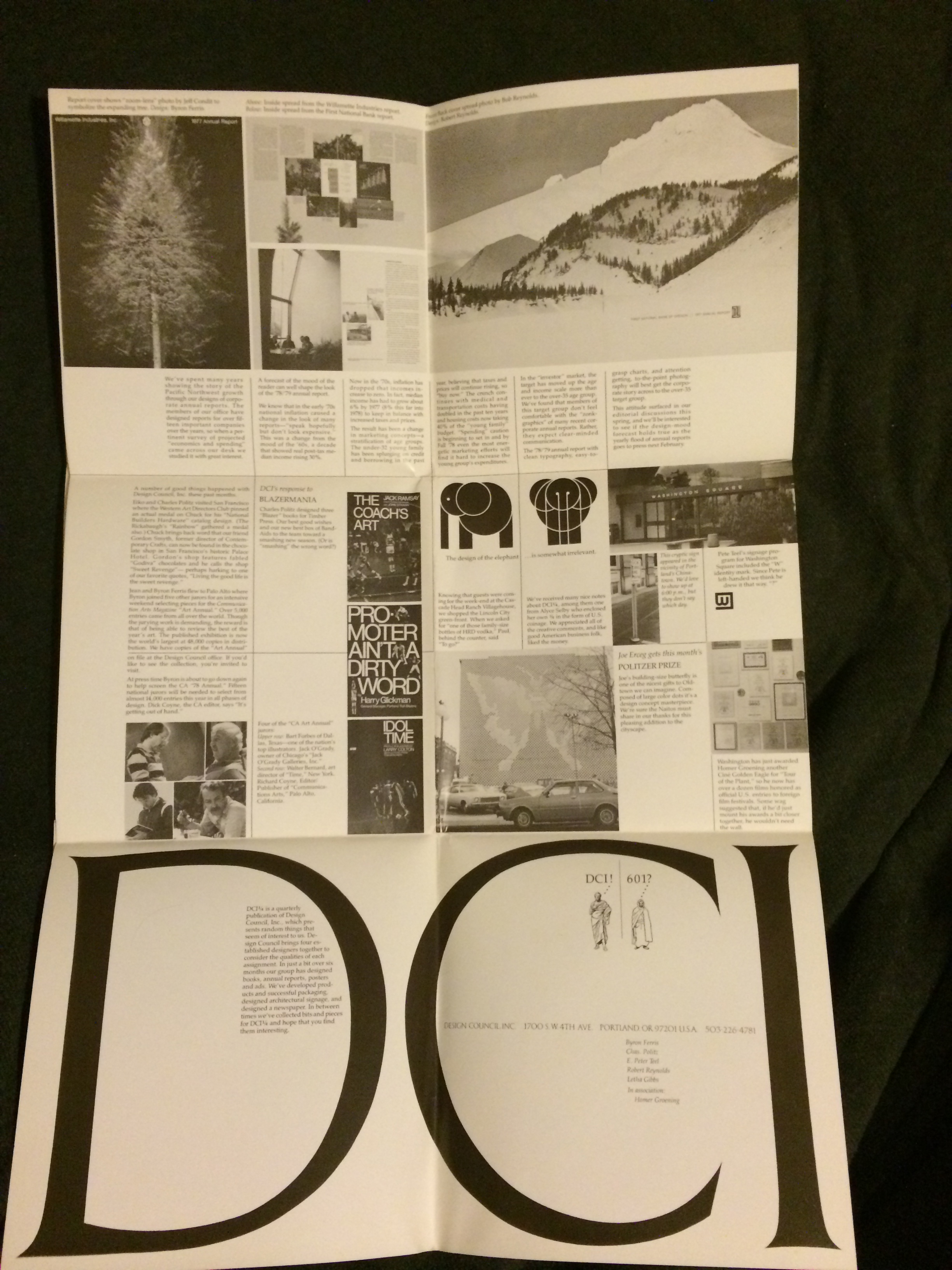

In 1976 Byron started another firm, this time with Charles Politz, Peter Teel and Robert Reynolds, called Design Council, Inc. (DCI). Their client list included Willamette Industries, Pacific Power & Light, Richard, Ltd., Zimmer Gunsul Frasca, and Boyd Coffee Co.

Byron was an advocate for design in the greater community. According to colleague Joe Erceg, Byron was involved in expanding the idea of good design throughout the city. “Byron started this thing as a part of the Art Director’s Club, that was the ‘Best Sign Award’. The group would nominate and vote for local businesses who had good sign design, and they would honor those businesses with an official award.”

Byron’s community work continued, and in 1983 when The Portland Ad Federation founded the first ever museum dedicated to the history of advertising in America, Byron Ferris was a founding board member. The American Advertising Museum was located in downtown Portland until 2004 and included displays featuring advertising from as early as the 18th century and one of the six original Jantzen Diving Girls once used at Jantzen Beach Amusement Park. Byron’s extensive knowledge of design history helped in crafting the museum’s exhibits, while his humor kept board meetings light. Byron impressed his fellow board members by drawing furiously throughout meetings — often cartoons depicting meeting attendees, like accountant & treasurer, Jim McDonald.

Jim McDonald balancing the books.

Dynamic Curiosity

In addition to learning the ins and outs of the ad business from Byron, Meridel absorbed from Byron a love for travel. “As a young person at Bachman/Ferris, I hung around at night, to learn from him. After hours, he got into showing me his travel slides of Paris and London—he had traveled all over the world—and I would drool over that. He would say, ‘All you have to do is save $25 a month for a year, and then you’ll be able to go.’”

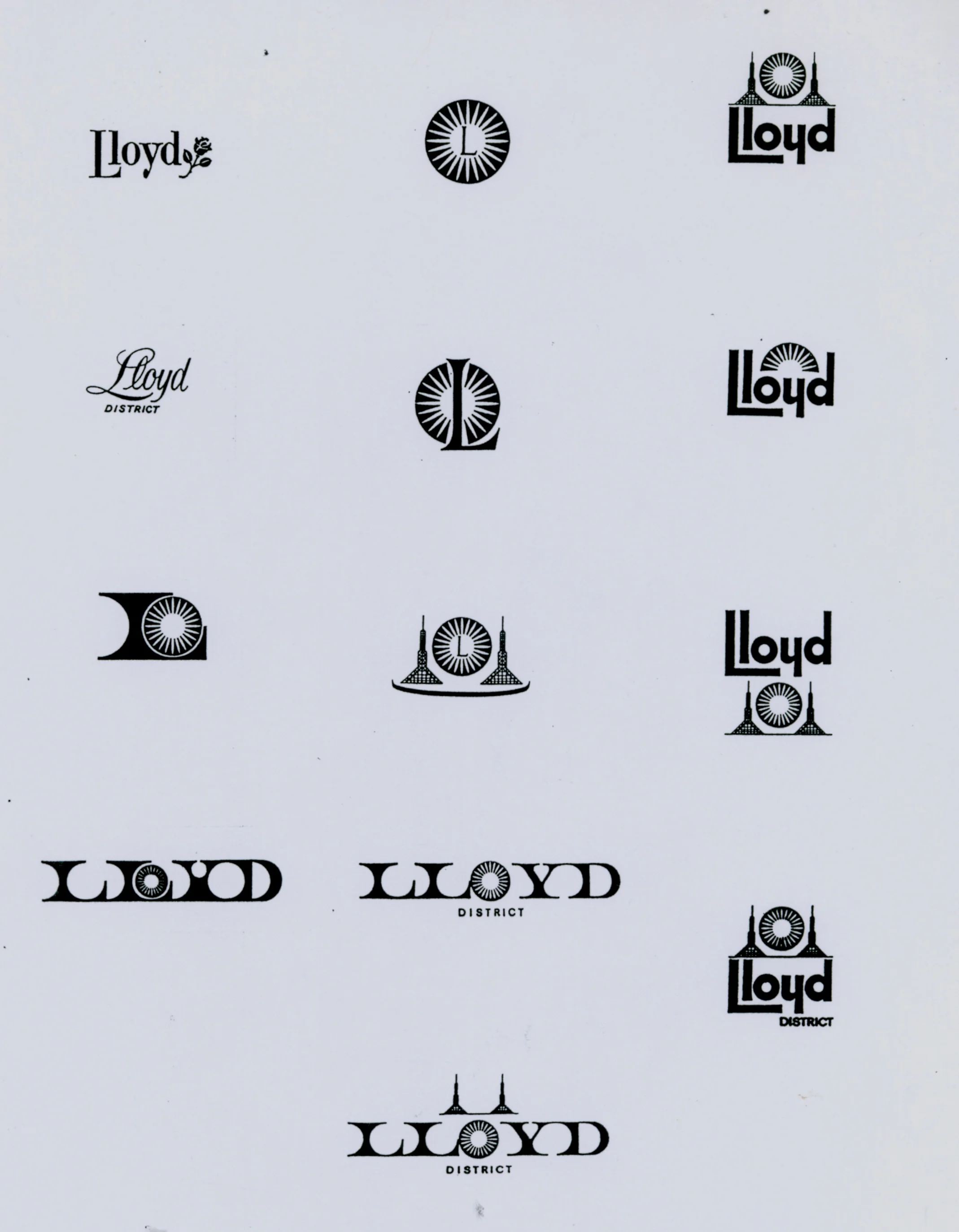

Logo options for the new Lloyd District in Portland

Byron’s innovative spirit let him to pursue and secure several patents, among them the klimamasek, a “hot nose” to cure the common cold (it never made it into clinical trials), and an improved photo wheel for use by graphic designers. Even in Byron’s retirement, he was still writing and creating. His creations included the books, “Jokes for Grandkids” and “The Four Jeffs” about his adventures with his pals.

Byron’s design work for Pioneer Square.

“Byron’s work lives on through the design students from his years at the Museum Art School (now PNCA) who carry forward his commitment to good design and to letterform," Carol Ferris said of Byron’s impact. “His commitment to design as a viable commercial art field laid a foundation in the 60s and 70s for the current inclusion of design thinking at PNCA.”

According to Carol, Byron believed, “that life as a designer meant carrying a dynamic curiosity and focus into all aspects of modern life. Byron was insatiably curious and widely read about many things, loved to travel, loved language, loved good food and wine, and yes, martinis.”

Thanks to Carol Ferris, Meridel Prideaux, Jim McDonald & Joe Erceg for their time, and to Eric Hillerns for connecting me to Byron Ferris when he spoke at an AIGA event in 2008.

Portland Design in the 1960s is a series developed by Portland designer Melissa Delzio. It was originally inspired by her Design Week Portland event titled “Portland Designers in the Mad Men Era”. Here’s a short list of 1960s designers we might feature next: Doug Lynch, Greg Holly, Dick Wiley, Joe Erceg, Timothy Leigh, Milli Eaton, Pier Mellara, Thomas Lincoln, Lloyd Reynolds, and Mark Norrander. If you have a recommendation on who we should feature, please reach out to: melissa@meldel.com.